Faricimab was recently approved by the FDA for the treatment of diabetic macular edema (DME). It is the first drug which simultaneously blocks vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) and angiopoietin-2 (Ang 2). The anti-VEGF-A action is shared with bevacizumab, ranibizumab, and aflibercept; and stabilizes microvascular permeability and inhibits neovascularization. The Ang 2 inhibition works via the angiopoietin and Tie signaling pathway to reduce microvascular permeability by a pathway independent of VEGF-A blockade. Preclinical studies suggested that faricimab might be more effective than simple anti-VEGF inhibition in treating diabetic macular edema. In particular, there were expectations for improvement over the status quo in duration of action. If similar efficacy with lesser treatment burden were possible, this would help overtaxed clinicians and patients and begin to close the real-world versus randomized trial performance gap.1

The results of two identical, phase 3 randomized clinical trials, YOSEMITE and RHINE, were recently published, allowing clinicians the opportunity to assess how the efficacy of faricimab matches the promise of the preclinical studies.2 There were 3 groups in the randomization: faricimab 6 mg q 8 weeks (F8), faricimab 6 mg with a personalized treatment interval (FPTI), and aflibercept 2 mg q 8 weeks (A8). The study authors reported the following in their paper:

- With A8 as the comparator, both F8 and FPTI were noninferior (4 letter margin) based on a primary outcome of mean change in best-corrected visual acuity at 1 year, averaged over weeks 48, 52, and 56.

- There were no differences in safety events among the 3 groups.

- In the FPTI group, more than 70% of patients achieved every-12-week dosing or longer at 1 year.

- Reductions in CST and proportions of eyes without center-involved DME (CI-DME) over 1 year consistently favored faricimab over aflibercept.

- Faricimab demonstrated a potential for extended durability in treating CI-DME.

Based on the evidence in the paper, are the claims substantiated?

With respect to noninferiority of mean change in best corrected visual acuity, the answer is qualified by the authors’ method of measurement. Because the three groups got last injections at different times, there was no single visit for which assessment of final visual acuity was intuitive. Therefore, the authors averaged the visual acuities measured at 48, 52, and 56 weeks. For the F8 group, the 3 components of the average were 4 weeks post-injection (the measurements taken at 48 weeks), 8 weeks post-injection (the measurements taken at 52 weeks), and 4 weeks post-injection (the measurements taken at 56 weeks), implying that the average last visual acuity was at 5.33 weeks post-injection ([4+8+4]/3=5.33). For the A8 group, the 3 components of the average were 8 weeks post-injection (the measurements taken at 48 weeks), 4 weeks post-injection (the measurements taken at 52 weeks), and 8 weeks post-injection (the measurements taken at 56 weeks), implying that the average last visual acuity was at 6.66 weeks post-injection ([8+4+8]/3=6.66). That is, the A8 group was disadvantaged relative to the F8 group by virtue of the F8 group having more injections in the first year, and an injection nearer to the outcome measurement times. This issue might have been averted had the F8 group received the same 5 initial monthly injections as the A8 group.

It is difficult to provide an analogous comparative calculation for the FPTI group. The relevant information is depicted in figure 3B, but the scale of the figure is microscopic, and only estimates can be made. For example, the YOSEMITE panel of figure 3B, the red-boxed subgroup, appears to comprise 63 patients. For these patients, the 3 components of the average were 16 weeks post-injection (the measurements taken at 48 weeks), 4 weeks post-injection (the measurements taken at 52 weeks), and 8 weeks post-injection (the measurements taken at 56 weeks), implying that the average last visual acuity was at 9.3 weeks post-injection ([16+4+8]/3=9.3). Likewise, for the RHINE panel of figure 3B, the red-boxed subgroup, appears to comprise 67 patients with the average last visual acuity at 9.3 weeks. At the other extreme of the figure (the bottom) sits the group of eyes that could never be extended beyond 4 weeks. For YOSEMITE and RHINE this group appears to comprise 19 and 23 patients, respectively. The average last visual acuity for these eyes would be 4 weeks. In between these extremes of the figure, one would need to do an analogous calculation for every row in the figure, pooling all the results for an overall average. This is clearly more than a reader can be asked to do. The authors should have done it and reported the result in the paper, to allow the reader to see if the outcome time for the FPTI group is comparable to the A8 group. The suspicion is that they are not comparable.

Regarding the claim that the safety results of the three groups were equivalent, we agree with the authors’ interpretation. There is no evidence that faricimab is less safe to use over the 52 weeks of follow-up reported.

The authors claim that over 70% of the FPTI group were able to enter the q 12 week dosing interval. The specific term they chose was “achieved” to signal this distinction. However, entering 12 week dosing is different from demonstrating that faricimab can sustain such intervals. The primary outcome at 52 weeks did not give enough time to determine if those eyes entering 12 week or longer durations could sustain that performance, or whether they would regress to require shorter interval injections. In YOSEMITE, 169 eyes (59%) and in RHINE, 172 eyes (56%) completed one 12wk interval to be assessed for successful completion. The reader has no idea if this proportion will be sustained in the second year of the trial, and it would be an unfounded assumption to expect the entrance to q12 week intervals to be maintained. This outcome will be of great interest when the 2-year results are reported. Only 22%/21% (Yosemite/Rhine) actually completed a 16-week interval and none were treated long enough to determine sustainability of this interval.

Another problem with the authors’ claim on duration of effect has to do with a form of spin, specifically type 3 spin, in the classification of Demla and colleagues.3 A reader might think that this achievement by faricimab distinguishes it from aflibercept, but that inference would not be warranted because of the study design. There was no aflibercept personalized treatment interval arm of the randomization, which would be required to make a claim that increased duration between injections was an advantage of faricimab. While true that a drug company investing in faricimab has no obligation to provide an opportunity for the competitor’s comparator drug to perform as well, the authors cannot claim that the feature displayed by faricimab is a differentiator worthy of a clinician’s choice as a deciding factor in the question of which drug to use. It is also true that the authors don’t make this claim differentiating the drugs, but in presenting asymmetric evidence as they do, an erroneous inference is easy to make, which we seek to avert.

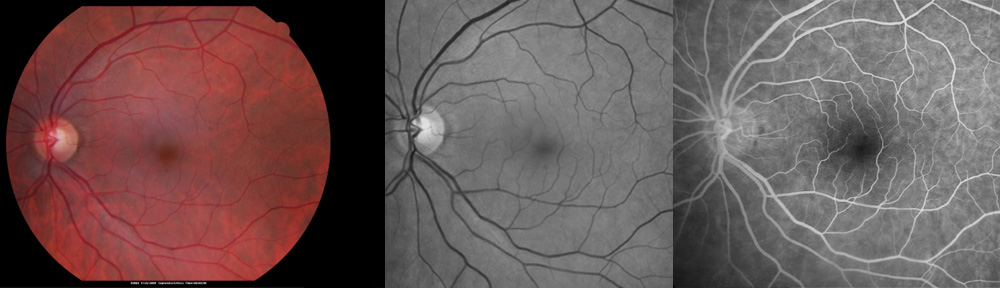

The authors’ claim of superior drying effectiveness for faricimab is supported by the presented data, but unremarked by the authors was evidence of similar durations of drying action of faricimab and aflibercept. To see this, examine figure 3C. The slope of the thickness curve trended toward a more rapid decrease in both arms of faricimab compared with aflibercept during the monthly injection stage (initial loading stage). In an analysis of the graphs after the loading stage (monthly injections), both faricimab and aflibercept showed a similar jagged curve demonstrating a drop-off of treatment effect during the no-treatment month. A jagged response is not seen in the FPTI group because the treatment intervals varied within that group. The zig-zag rebound of edema seen in both faricimab (F8) and aflibercept (A8) groups suggests the durability of the treatment effect may be similar between the two drugs. These studies did not perform a direct comparison of faricimab and aflibercept on the same personalized treatment interval protocol.

The authors’ contention that faricimab rendered a higher proportion of eyes free of CI-DME is warranted by the data they present.

Finally, the authors emphasize the potential of faricimab for lesser burden of treatment because of potential longer durability. This emphasis is unsupported by the evidence presented. The F8 group received 10 injections. The A8 group received 9 injections – hence no decreased burden favoring faricimab over aflibercept in this comparison. It is more complicated to analyze in the FPTI group because the needed information is not reported, but we can make some inferences. There were 63 eyes of 286 (22%) in Yosemite and 66 eyes of 308 (21%) in Rhine that achieved the opportunity to extend treatment; these eyes underwent a total of 8 faricimab injections at week 52. This number represents the least number of scheduled injections and only one less than the aflibercept group. The remainder of eyes were scheduled to have more than 8 injections, but the pooled average is difficult to parse from figure 3B. We can easily note that from the figure that the greatest number of injections at week 52 in this arm of the study was 14 injections in eyes that required monthly treatment (19 eyes (7%) in Yosemite, and 22 eyes (7%) in Rhine). This is far more than the 9 injections of A8, and does not demonstrate a reduced treatment burden among eyes in the faricimab group compared with aflibercept. When the remainder of eyes between the extremes of figure 3B are added in to the calculation of average treatment burden, which we encourage the authors to report, we suspect that it was greater for the FPTI arm of the study than for A8, not less.

In summary, YOSEMITE and RHINE provide data that faricimab as administered in the studies was equivalent to aflibercept in the primary visual outcome, and superior to aflibercept as given in the study in drying the macula. No data were presented supporting a claim that treatment burden is less with faricimab than aflibercept. The published data show that a proportion of eyes can be managed with a reduced injection burden with faricimab, but provide no evidence that this would differentiate faricimab from aflibercept were aflibercept plugged into the same personal treatment interval algorithm. There was no arm of the study that would allow such a comparison to be made. The published data substantiate that faricimab has a greater macular drying effect than aflibercept, but the see-saw central subfield thickness curve in the non-loading phase of the first year suggests that the duration of drying by faricimab is no greater than with aflibercept.

The FDA has approved faricimab for the treatment of CI-DME based on YOSEMITE and RHINE. Retinal specialists will be making choices of which drug to use. An economic perspective will enter into the decision. The clinical decision will not be based exclusively on efficacy. The offered average costs for aflibercept and faricimab to the editorialists are $1747 and $2168, respectively. Is the $441 differential cost a reasonable price to pay for the documented differences in drug performance? Our opinion is no. There is no published difference in visual outcomes, nor any published difference in durability, because it wasn’t checked. There is a difference in macular drying, analogous to the superior drying effect of aflibercept over bevacizumab in the better-vision group of protocol T (eyes with CI-DME)or in the aflibercept versus bevacizumab group in SCORE-2 (eyes with central retinal vein occlusion with macular edema).4,5 We, and many others, did not think that differences warranted the use of aflibercept over the less expensive bevacizumab in cases similar to those in the better seeing group of protocol T or eyes like those studied in SCORE-2, nor do we think that drying difference seen in YOSEMITE and RHINE between faricimab and aflibercept is reason to choose the more expensive drug. We congratulate the authors of these studies for providing ophthalmologists with new options for treating diabetic macular edema, but nothing they have published suggests that this option marks a milestone in reducing treatment burden in DME. The 2-year results will be more informative for decision-making than the 1-year results, and we encourage the authors to remedy the flaws in their year -1 results data presentation so that the 2-year data are more useful.

By David J. Browning, MD, PhD and Scott E. Pautler, MD

References

1. Kiss S, Liu Y, Brown J, et al. Clinical utilization of anti-vascular endothelial growth-factor agents and patient monitoring in retinal vein occlusion and diabetic macular edema. Clin Ophthalmol 2014;8:1611-1621.

2. Wykoff CC, Abreu F, Adamis AP, et al. Efficacy, durability, and safety of intravitreal faricimab with extended dosing up to every 16 weeks in patients with diabetic macular oedema (YOSEMITE and RHINE): two randomised, double-masked, phase 3 trials. Lancet 2022;DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00018-6.

3. Demla S, Shinn E, Ottwell R, Arthur W, Khattab M, Hartwell M, Wright DN, Vassar M. Evaluaton of “spin” in the abstracts of systematic reviews and meta-analyses focused on cataract therapies. Am J Ophthalmol 2021;228:47-57.

4. Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network, Welss JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, Jampol LM, Aiello LP, Antoszyk AN, Arnold-Bush AN, Baker CW, Bressler NM, Browning DJ, Elman MJ, Ferris FJ, Friedman SJ, Melia M, Pieramici D, Sun JK, Beck RW. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1193-1203.

5. Scott IU, VanVeldhuisen PC, Ip MS, et al, SCORE2 Investigator group. Effect of bevacizumab vs aflibercept on visual acuity among patients with macular edema due to central retinal vein occlusion: the SCORE2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;317:2072-2087.

Like this:

Like Loading...